I took a stroll through Ducati SA’s Centurion premises a short while ago ogling all the Duc’s on display. I am a long time Ducati fan and yet strangely [especially for me, my mates would say], have never owned one. I even worked at Continental Cycles in Main Street in Johannesburg in the early 1980s for a while before leaving what was then a very fickle motorcycle industry. One of the bikes on display is a race-prepped Ducati Pantah, still in it’s Presto Parcels livery as ridden with such distinction by the Petersen brothers, Dave, Robbie and the late Keith.

Raced in both the 750 and 500 class, the Pantah’s handled and braked so well that they became a dominant force in those classes. Down on power, despite the best efforts of Ricardo Frisoli at Continental Cycles, they became giant killers in the talented hands of the ex-Rhodie Petersens. This got me thinking back to another giant-killing performance by a brace of factory racing Ducati’s.

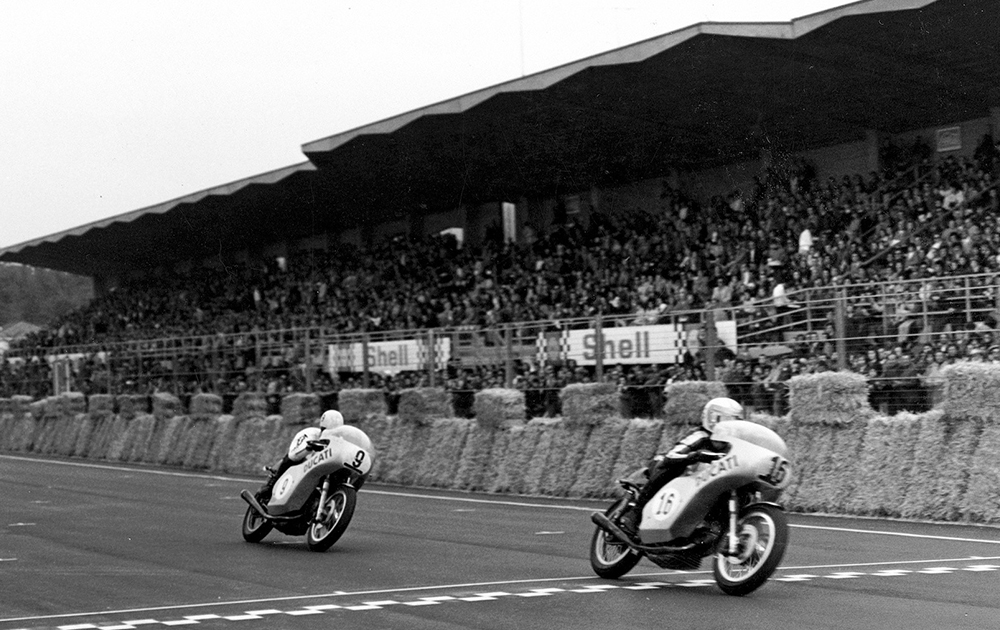

The year was 1972 and the place was the circuit Dino Ferrari at Imola in Italy. Today we simply refer to the circuit as “Imola”. The first 200-mile race ever staged in Europe was run at this circuit in April of 1972. Grand Prix racing had a 500cc limit but the “bigger is better” Americans raced 750cc four strokes in their AMA Series and specifically at Daytona.

The American market was so important to all the factories that they built factory racing 750cc four strokes and two strokes to compete for glory at Daytona. A perfect example of this was Dick “Bugsy” Mann, tempted by Japanese money from his 1969 Daytona winning BSA Rocket Three factory bike onto the new Honda CB 750 Four for 1970. Honda wanted to emphasise the mechanical superiority of their new Four to the American public by winning Daytona. History tells us that they won, with the only factory Honda to finish the 200-mile race. The other two factory bikes both expired with cam chain failure, an issue that plagued racing Honda’s for some time.

In Europe, the new formula allowed over 500cc two strokes or 750cc four strokes. Smaller than 500cc’s was not allowed, specifically I think, to exclude the extremely fast, nimble and reliable water-cooled Yamaha TZ 350 Twins which had humbled the 750’s on a few occasions. The real spectacle was the big booming four strokes. At Imola, there were a number of factory supported bikes. Triumph and BSA had a few Trident and Rocket based triples on the starting grid ridden by stalwarts like John Cooper, Percy Tait, Alan Jeffries and Ray Pickrell.

Peter Williams and Phil Read were on John Player Norton’s. Dave Simmons was on a 517cc Kawasaki H1 triple, its two-stroke rasp drowned in a sea of four-stroke sound. The legendary Giacomo Agostini put his 750 factory MV Agusta four on the front row, shaft drive and all. The bellow from the four black megaphones was otherworldly. A solitary 750 Kawasaki Triple was entered by Americans Cliff Carr and techno fundi Kevin Cameron. Moto Guzzi had a pair of 750 v-twins which were really mildly modified street bikes with big carbs and slippery fairings, somewhat outgunned by the other factory-supported machines. Honda was represented by Roberto Gallina with what was the strongest privateer Honda in Italy. [Honda only ever raced once as an official factory team when they won Daytona in 1970, but supplied HRC go-fast goodies to privateers]. Walter Villa, who won a World 250 Championship on a factory Harley-Davidson, was also on a Triumph Triple. One two on the starting grid were the stars of this story, the two factory Ducati SuperSport 750 racers ridden by Italian legend, Bruno Spaggiari and the Brit, Paul Smart. Smart was actually down to ride a Triumph at Imola, only to have his ride pulled by Triumph due to factory politics. Ducati offered him a literal last-minute ride, which he accepted, “just to earn the start money”.

Smart flew to Bologna to get acquainted with the Ducati racers the week before the race. Let’s look at the bikes for a moment. The 750SS and 900SS Ducati’s were the brainchild of Ducati design Supremo, Dr Fabio Taglioni. He was the pioneer of their use of “desmodromic” valve gear, which essentially opens and closes the valves mechanically, as opposed to using valve springs. [A loop spring simply closes the valve to allow starting compression, where after a complex set of rockers open and close the valves with precision].

Taglioni visited Daytona to witness the formula 750 bikes in action and to asses what they were up against. He was very impressed by the Japanese onslaught, however, he realized that Ducati neither had the time or the resources to go toe to toe with the Japanese juggernauts. He would never beat them at their game but he could employ a simple formula of his own. Without scores of computers [he joked that he couldn’t even switch one on] and technicians to do his bidding, he fell back on a tried and tested Ducati strategy. He started with the blank canvas which was his 750 SS sports bike. Taglioni was an intuitive designer. One of those rare individuals who has a “feeling” for what will work. His successful 350cc singles were testimony to that, having won notable races like the Baja 1000 in Scrambler guise. He knew that he could not match the horsepower of the multi’s but he also knew that it was not just straight-line speed that won races. What he wanted was balance!. Handling and braking must match usable horsepower.

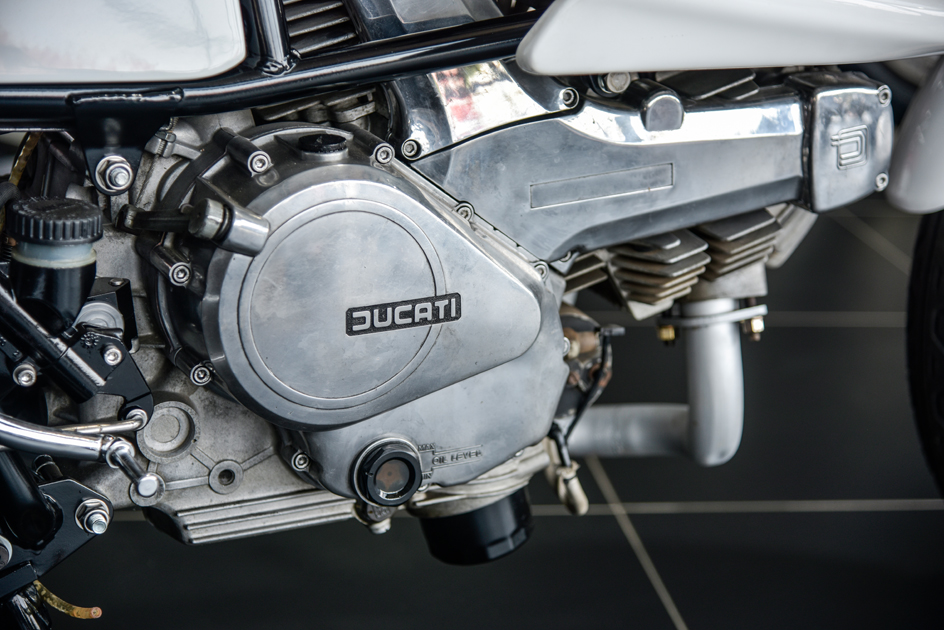

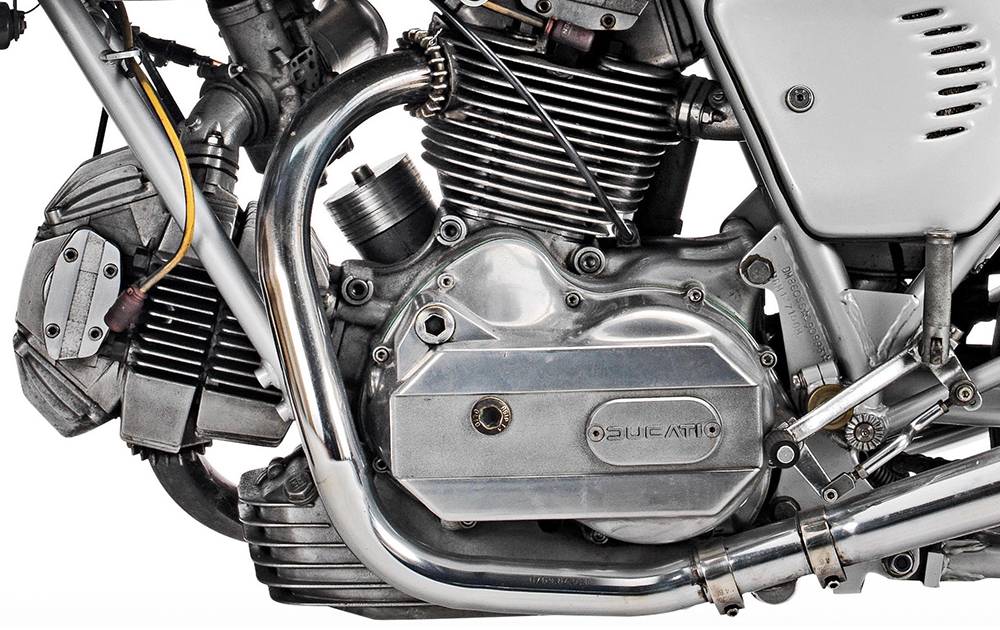

The eerie thing is that the bikes were really very close to standard!. An 80mm x 74mm oversquare bore helped the 750 rev without silly piston speeds. 40mm concentric Dell’Orto carbs would feed the beast through five-inch manifolds. Heads were two valve units, with a 40mm inlet and a 36mm exhaust valve. Big valves like this are prone to “bounce” at high revs, hence the need for desmo control. Each cylinder had its own overhead cam driven by a bevel gear shaft off the crank. Compression was bumped to 10:1 and the motor revved reliably to 9,200 rpm. Cylinder head temperatures were controlled by using two spark plugs and an oil cooler was fitted for good measure. Concerned with questionable reliability, Taglioni forsook electronic ignition in favour of a “total loss” battery and coil system with contact breaker points. The crankshaft was stock standard, as was the gearbox and clutch, apart from the clutch housing being drilled for weight reduction. Conrods were machined from forged billet to ensure high rpm reliability.

Frames were stock standard. The front forks had an additional disc and Lockheed caliper grafted on, to double the front braking power over that of the road bike. Forks were off the assembly line. Running the tallest gearing suitable for Imola the bikes were geared to run 169 mph in top gear. Not too shabby for an essentially stock 1972 motorcycle. Ready to race, the bikes weighed 392 pounds, or in modern metric speak, around 179 Kg’s. Lighter and slimmer than the multi’s, the Ducati made much of it’s 84 rear wheel horses @ 8800 rpm. Significantly, it was making 70 at 7000 rpm, which coupled with the torquey nature of the twin allowed it to punch out of the turns with meaning.

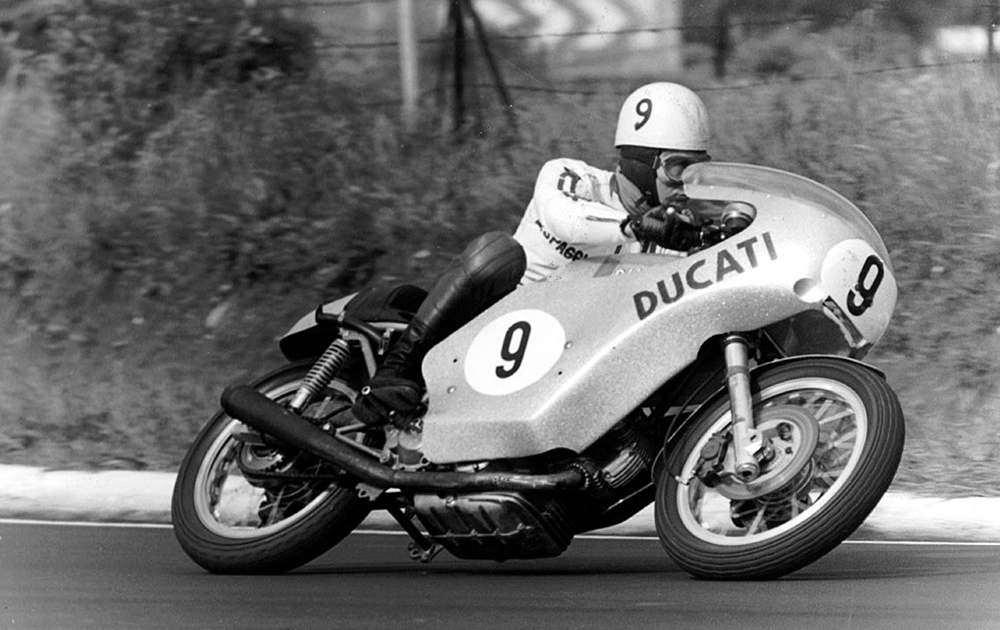

Bruno Spaggiari put the 750 Duc on pole, with his teammate Smart alongside him. The 517 cc Kawasaki Triple of Dave Simmonds in third relegated Ago’s MV to the final place on the front row. The second row consisted of the sweet handling but down on power Norton’s, the privateer Honda and Walter Villa on the fastest of the Triumph threes. At the drop of the flag, Ago blasted the MV Four into the lead followed by Smart with a pack of multi’s hot on his heels. The Americans were finding Imola very different to Daytona where horsepower is king. Paul Smart put it best “You’d better know how to ride, and you’d better not be out there on something that’s just a heap of horsepower and a bloody gate”. American Don Emde, on a Norton, echoed Smart saying “Imola is super neat. It’s really fast; it’s a mind-blower it’s so fast, and there’s nothing quite like it back home”. By lap four, Spaggiari had sliced and diced his way into third and into Smart’s draft. Agostini was leading.

The race settled into a Ducati one-two with the lone MV around 10 sec astern. Gallina’s Honda lay in fourth until it’s motor let go on the17th lap. All the while, the two Duc’s bellowed around the track at a smooth and steady 100 mph average. Ago sat 8 seconds off the Ducati’s for 42 laps until the gearbox on his MV said “enough”. With 50 miles to go, the crowd started sensing a Ducati victory. If only the bikes would hold together. Villa on the Triumph inherited third from Ago and was lapping fast and consistently. The pace at the front now became frenetic. Spaggiari and Smart had a gentlemen’s agreement, for the sake of Ducati, not to race each other. They agreed to share prize money if it came down to a two-man race. With 50 miles to go, that agreement went right out the window. Try and tell an Italian legend, riding at his home track, in front of a partisan crowd, that he must settle for second.

The Ducati duo went at it hammer and tongs, neither giving an inch. All the while the Ducati faithful in the pits and in the crowd prayed that the race gods would smile on them. Imagine the two taking each other out within sight of victory and a Ducati 1st and 2nd to boot? Spaggiari forced his way into the lead but under continuous pressure from Smart glued to his slipstream ran wide in a fast sweeper on the last lap. For Smart, it was now or never. He muscled his Ducati inside the luckless Italian and held the lead over the last mile and a half to the finish. The crowd went ballistic! They mobbed the two Ducati pilots. For the moment Smart was an honorary Italian. The fairy tale had its magic ending. At home, Italian honour was upheld. Ducati took on some of the best in the world and beat them emphatically. The victory meant so much to Ducati that, in the fullness of time, they built a “Paul Smart Replica 1000 LE” in the same silver and green colours of the original Imola winning 750’s. Paul Smart wrote himself into the annals of motorcycle racing history with his spectacular win.

This story sums up what you get when you acquire a Ducati. You are not just buying a bike. You are getting a rolling piece of two-wheeled Italian passion with a long and illustrious history. Every time that Desmo V-Twin fires up it carries some of the Spirit of Imola in its staccato rumble.