Did Harold Daniell, when he won the inaugural round of the Motorcycle Grand Prix World Championship, the Senior TT on the Isle of Man in 1949, have any idea how the bikes, the riders, the tracks and even the World Championship as a whole would develop in the next 74 years? Did he even give it a thought?

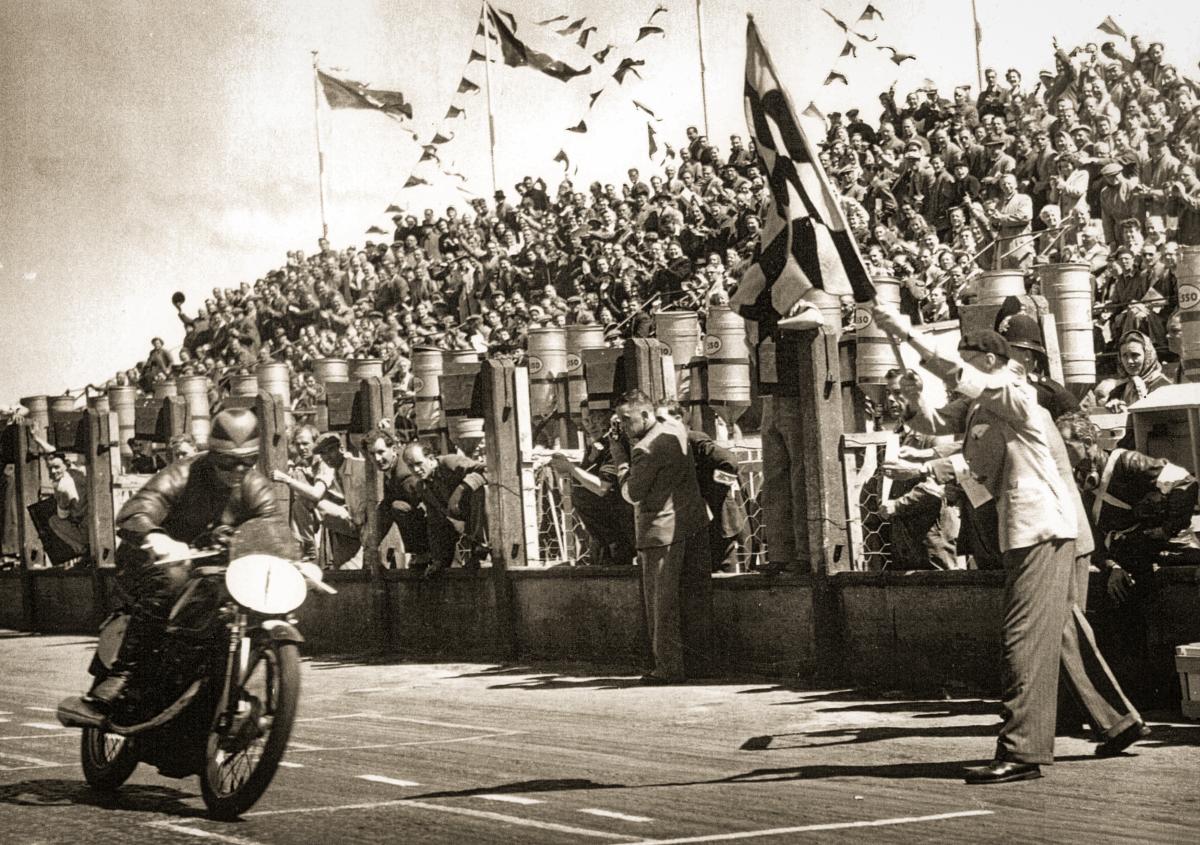

1000 races later at the Le Mans circuit, we were treated to a brilliant race that was both a million miles from that first race and, at the same time, not all that different: Le Mans 2023 was still a test of man and machine against his fellow competitors and the race track itself, only the details had changed.

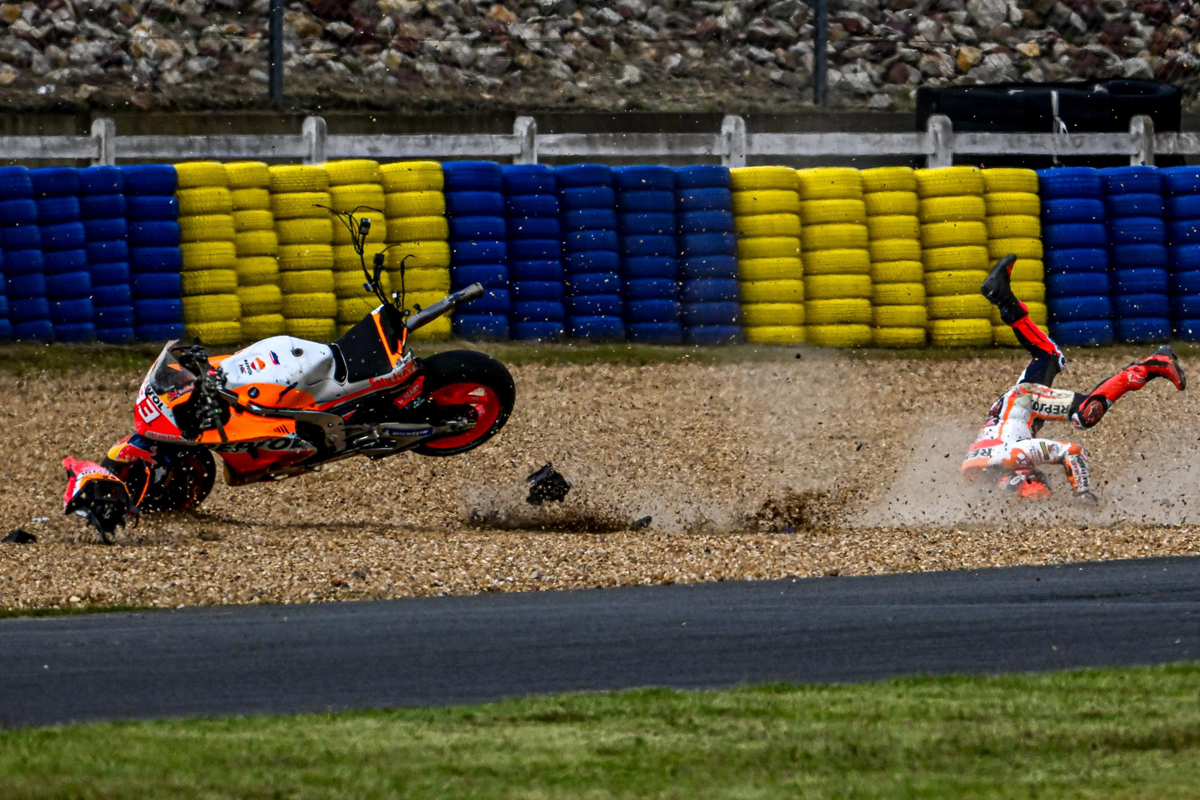

Yet again, it is a case of where to begin. Martin’s debut victory in the Sprint race? Bezzecchi’s imperious victory in the main race? Viñales’ and Bagnaia’s contretemps in the gravel? Alex Marquez scuttling out of the way on all fours after his crash with Marini? Binder getting pushed wide on the first lap and recovering from 18th to sixth, despite a long lap penalty? Marquez riding about fifteen levels above the Honda to fight at the front? Fernandez finishing fourth on the GasGas? Jack Miller throwing it up the road in both Sprint and Main race while fighting at the front (“I was a f***ing idiot”)? More anger directed at the stewards? Oh, the glory that is MotoGP in its 74th season.

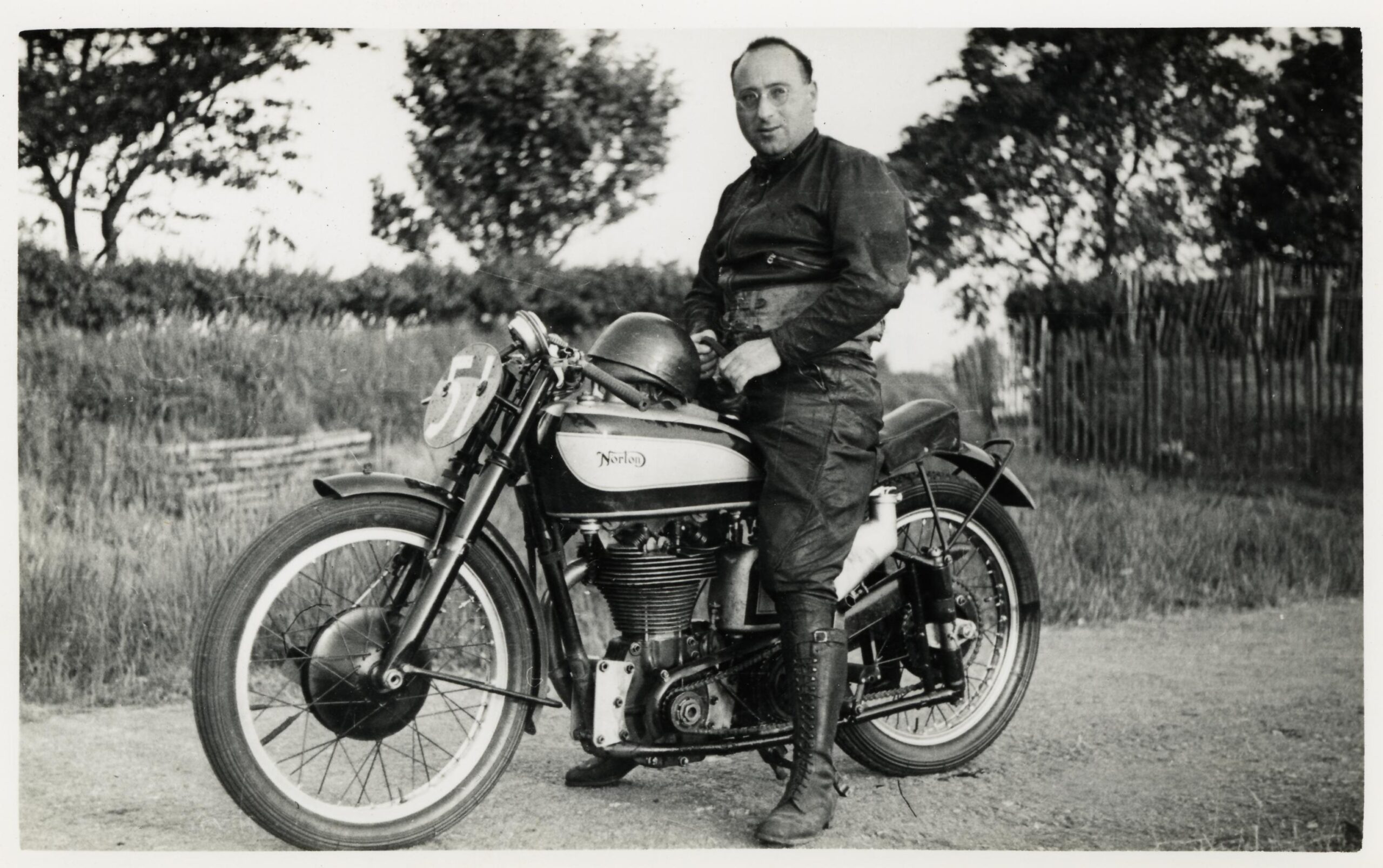

In 1949, Harold Daniell was a tubby, bespectacled racer riding a Manx Norton around what is today the most dangerous racing circuit in the world (although ironically, it was certainly not the most dangerous in 1949) for little more than the glory. His Norton’s 500 cc single-cylinder engine produced perhaps 50 horsepower and after the TT race week had finished, he probably went back to his day job until the next race came around (only six races in the championship that year).

How do you compare that with today’s multi-millionaire riders piloting insanely technologically complex, 300bhp+ missiles at speeds of up to 350 km/h, I do not know. But the premise is exactly the same: be the first rider home. It’s just that nowadays, we have incredible access to every millimetre of the race from the rider’s perspective. How I would love to watch onboard footage from that first GP.

The other hugely significant advance has been in both rider and, more importantly, circuit safety. Over 100 crashes during a race weekend are not unusual and, yet, the vast majority of them involve nothing more than a headache for the overworked mechanics. At worse, death is never far away in motorsport, although thankfully it is now the exception rather than the rule but, more often than not, the worst a rider will suffer is acute embarrassment at binning it yet again in front of his adoring home crowd.

I don’t think we can fully appreciate, from the comfort and safety of modern circuit design, the dangers of road racing circuits of the 1920s to the 1970s. Well, maybe we can: the Isle of Man TT is about to take place (last week of May, first week of June) and if ever there was an illustration of what riders faced week-in, week-out, throughout a racing season (which included many non-championship races as well as Grand Prix), then it is there. If today’s racing motorcycle covering a lap in less than 17 minutes at an average speed of 135mph+ in 2023 is legalised insanity, at least the bikes, the suspension, the electronics and the tyres are up to the task. Harold Daniell’s first sub-25 minute lap (average speed 91mph) in 1938 on a rigid-framed Norton, with treaded tyres and no “handling” to speak of, let alone brakes, on sketchy road surfaces, wearing the most rudimentary protection and a piss-pot helmet with goggles, is surely a more heroic feat?

The death rate in Grand Prix racing in those days was appalling. It wasn’t unusual for several riders to be killed every season and not all of those were back-markers: no one was immune. And yet, today, a rider will crash at 300 km/h and simply walk away, more often than not straight back to the pits to continue the day’s work. If that isn’t progress, then I don’t know what is.

Detractors of modern racing circuits, citing their cut-and-paste layouts and huge run-off areas are simply not living in the real world. You could argue that Grand Prix racing – on two wheels and four – only survived the deadly years because of the lack of coverage of the races – there was certainly no television. Also, remember that the world had recently come out of six years of bloody war, with millions of deaths on either side so people simply were not squeamish. Imagine today’s audience witnessing five fatal accidents on the race track every season. The sport would be banned forthwith and I doubt there would be many dissenting voices.

But this opens up a different can of worms, one that is regularly aired at the Isle of Man TT races. It is not unusual for two, three, or four riders to lose their lives every year and yet the TT remains, a last bastion of free will. And that’s the point: no one is forcing them to race: if someone chooses to risk their lives without endangering others, who are we to say otherwise?

But that is an argument for another day. For now, let’s just rejoice in the MotoGP racing we are privileged to witness today while respecting the past and celebrating our heroes. Here’s to the next 1000 races: what will MotoGP look like in 2097?