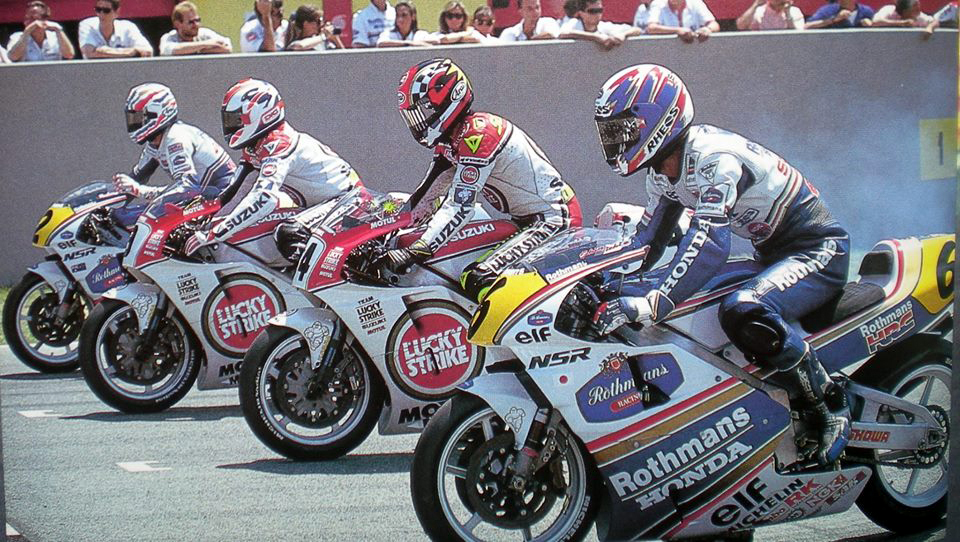

Back in 2003 MotoGP saw the end of the 500cc two-stroke era in favour of the mighty 1000cc four-strokes. It also saw the introduction of massive strides in electronics, where riders could depend more and more on features like adjustable traction control and wheelie control which helped to tame the Beasts huge power and torque. I remember watching Sete Gibernau exiting a 220 kph sweep, on worn-out tyres on his RC211V Honda, with the bike tracking like an XR 750 Harley on a dirt oval, smoke pouring off the back tyre. Everything kept nice and tidy by the riders skill and a huge dollop of electronic intervention. Let us wind back the calendar 10 years, to 1993.

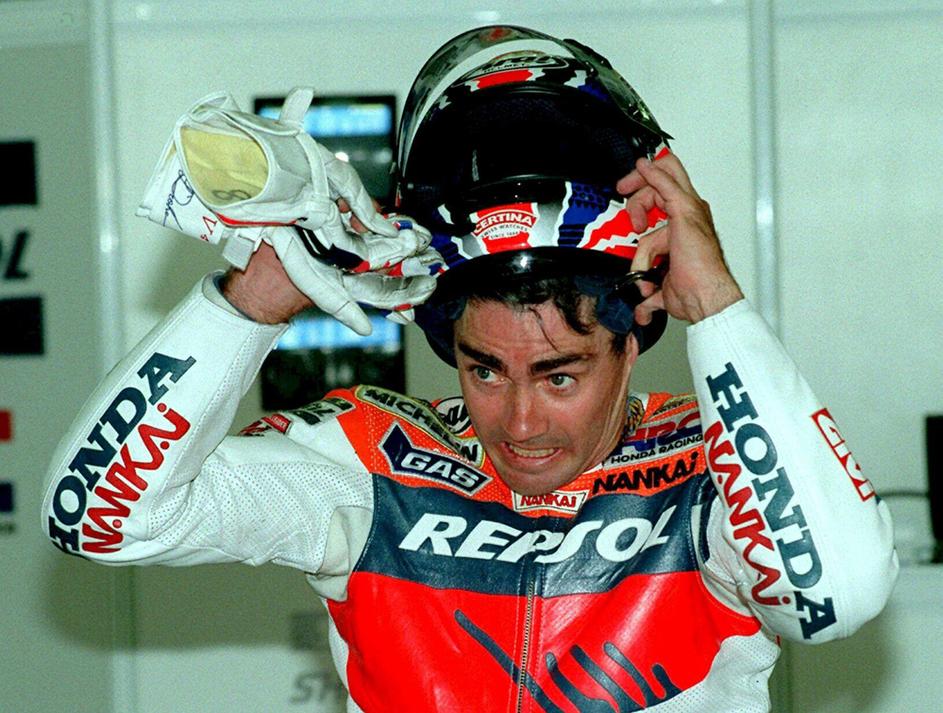

The next five years of MotoGP were dominated by an Aussie cobber by the name of Mick Doohan. As awesome a talent as ever pulled on a set of race leathers. He won those titles [1994 to 1998] against some of the finest riders that the world has ever seen! Cadalora, Capirossi, Schwantz, Barros, Criville, Gibernau, Abe, Puig, Kocinski, Bayle, Crafar, Checa, Biaggi, Gobert, Beattie, the list goes on and on. No one who watched these gladiators do battle will ever forget the spectacle. We are going to take a look at what is arguably the best 500cc racebike of all time, and then try and describe what it was like to ride it.

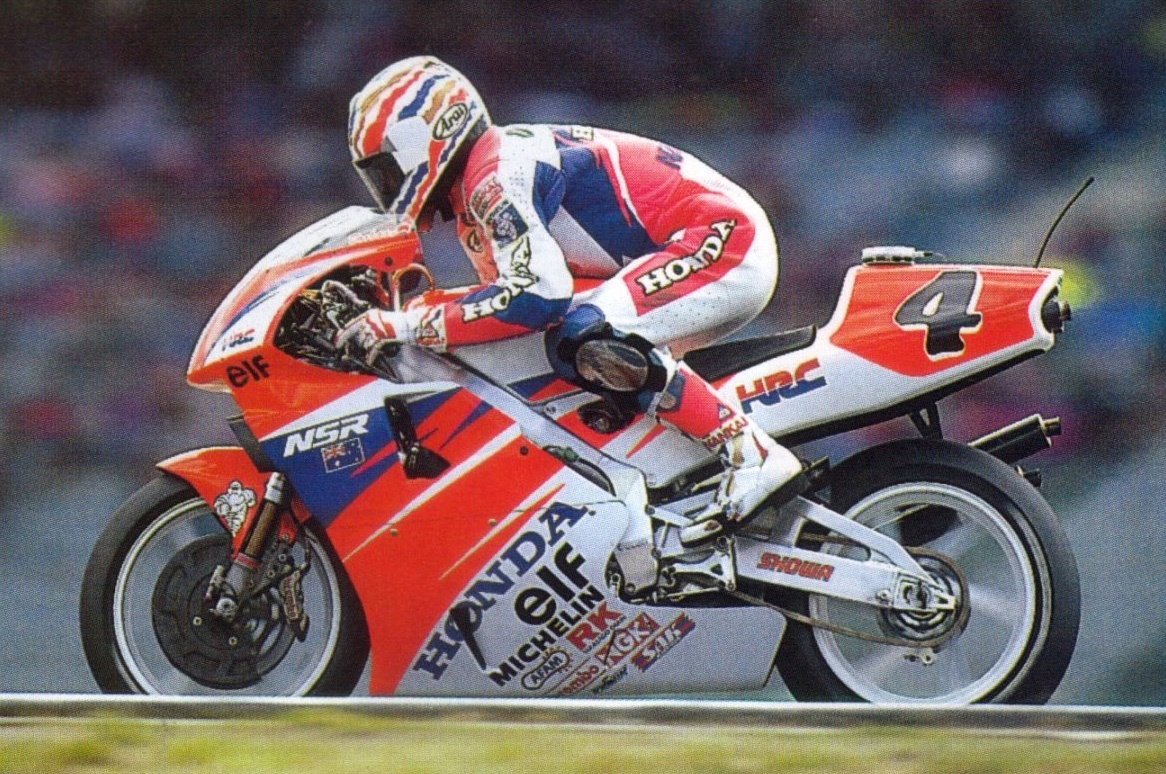

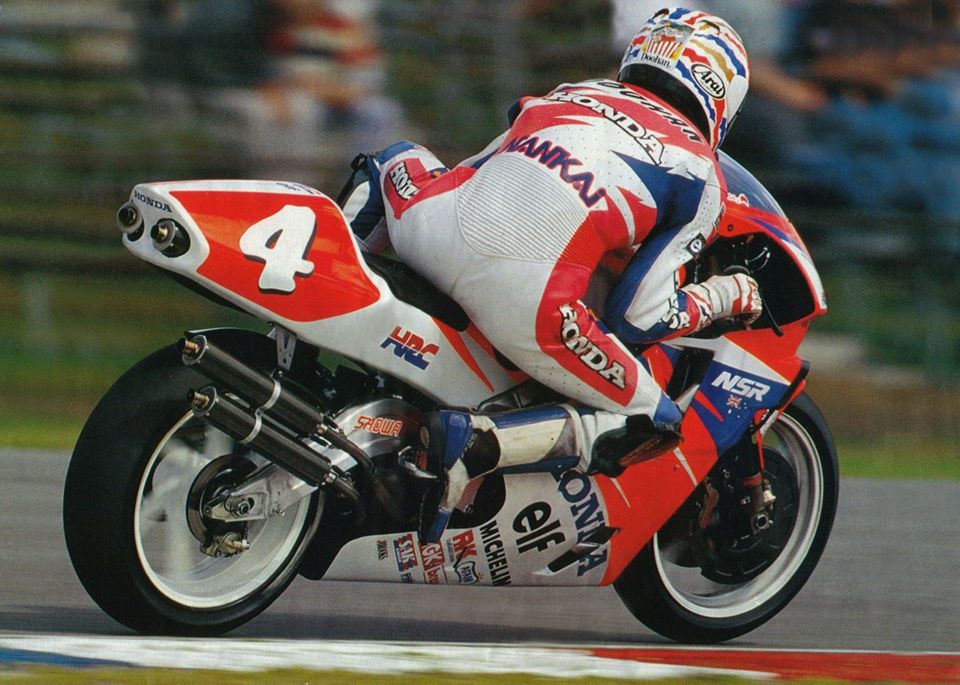

The Honda NSR500, as ridden to victory by Mick in the 1994 championship was a fearsome beast! Let’s look at some technical features. The bike under scrutiny is Mick’s own bike on which he won nine of the fourteen races making up the 1994 season. He was on the podium in the other five. Phenomenal!

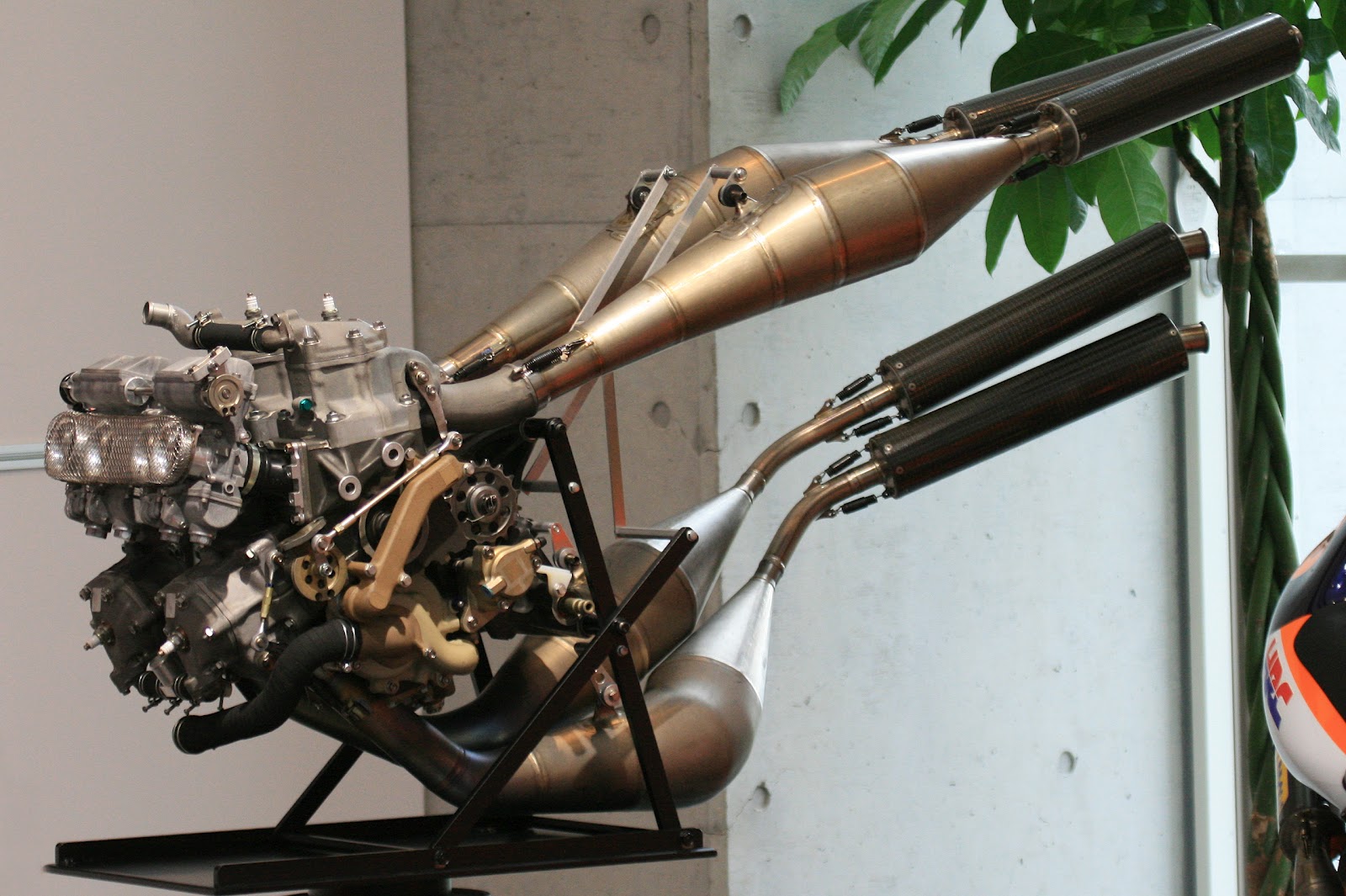

Honda revolutionised 500cc two-stroke engine technology when they introduced their Big Bang engine back in ’92 [Triumph have used the same technology in their new 900 Rally Pro Adventure bike for the same reason that Honda adopted it back then, for better traction]. The 500’s were very powerful, over 200 hp, and light, which made them prone to wheelspin. When they broke traction, it was instantaneous. Doohan explains, “On a 500, the tyre breaks loose at 8000 rpm; before you shut the throttle, it’s at 12000.

Compared to a Superbike, the torque of the two-stroke engine and how quick they respond because of their lighter weight makes the 500’s far more dangerous”.

The Big Bang technology alters the firing order to allow around 290 degrees more crank rotation before the next power stroke, allowing the back wheel to hook up. It did not gain power or torque but changed the way the power was delivered. Shinichi Itoh, on his NSR500, was the first GP rider to break 200 mph [324 kph] in 1993. Itoh’s bike had fuel injection, which gave better fuel consumption, however, Doohan ran his NSR with carburettors, as he preferred the “feel”.

The chassis on Doohan’s bike changed very little from 1991, with which, despite testing various options over the years, was always what Doohan was most comfortable with. The bike could be quick-shifter equipped, but Doohan liked a conventional setup. The bike had a sophisticated data acquisition system which monitored throttle opening, rpm and gear change points so that the bike “knew” where the rider was on a given track. It would then adjust the suspension rebound and compression damping rates accordingly. Once again, Doohan ran a conventional setup, whereas his teammates utilised the trick technology. The bike featured an exhaust water injection cooling system which helped to boost the torque in the 6000 to 10000 rpm range. Again, Doohan found that this power boost did not complement his riding style and his bike did not have this feature. The fairing extended as far forward as the rules would allow, so as to achieve a high level of downforce in an attempt to limit the high-speed wheelies to which the 500’s were prone.

Let’s look at the spec’s of the ’94 NSR500 and then hear what it was like to ride.

’94 NSR500 Specifications

| Price: | $1,000,000 [In 1994] to lease for a season, not for sale at any price |

| Engine: | 499cc, Liquid-cooled, 112-degree two-stroke V-Four |

| Carburetion: | 2 X Dual-throat 36mm Keihins |

| Suspension: | 43mm inverted fully adjustable Showa forks with Showa damped Honda Pro-link rear |

| Front brake: | Twin 290mm discs with four-piston Brembo calipers |

| Rear brake: | Single 196mm HRC steel disc with HRC two-piston caliper |

| Wheels: | 17″, 120 front and 180 rear, shod with Michelin slicks |

| Wheelbase: | 1405mm |

| Fuel capacity: | 32 litres |

| Weight: | 130 Kg’s [dry] – 165 Kg [fully fueled] |

| Power: | Over 200 hp |

Try and get your numbed brain around a 165 Kg [fully fueled], 200 hp missile with a 1405mm wheelbase, with essentially no electronics to help save your sorry butt! Ally that to the most viciously fearsome power delivery in all of bikingdom, and you have the stuff that cold sweats and dirtied rods are made of!. So what was it like to ride?

At the end of the ’94 season, selected journalists from the world’s most prestigious magazines, with experience from racing high horsepower bikes, got the opportunity to ride the NSR500 around the Suzuka circuit in Japan. Let us see how Sport Rider Magazine’s road test Editor Lance Holst, described his experience.

“After a few years of guest riding top race bikes with suspension settings that ranged from taught to nearly rigid, and engines whose radical state of tune and narrow focus had them alternatively spitting and barking at anything below race rpm, the civility of Doohan’s machine is disarming. I was expecting a beast, but as I roll down Suzuka’s pit row, pull in the surprisingly low effort clutch and engage first gear I’ve yet to find it. The engine responds smoothly from well below 6000 rpm and pulls cleanly with none of the high-strung behaviour you’d expect. In fact, the Big Bang engines are known for their droning engine notes sounding more like a big-bore motocrosser than the piercing, high-pitch shriek of the previous engine.

The seating position is roomy with a wide saddle, relatively low footpegs and clip-ons that aren’t too radical. The NSR is probably more comfortable than a Ducati 916 or Suzuki GSXR-750. Braking lightly for turn one, the carbon discs offer very little bite until they’re hot, and at my cautious pace, it takes a full lap to get them up to operating temperature. It is so low effort to turn the bike that it almost feels that the bike falls into the curves on its own, but with enough steering linearity that it inspires confidence. With the revs between 6000 and 8500, throttle response is superbly clean as I climb up through the left-right-left-right esses. Even the slightest throttle openings generate more acceleration than I expect, and I’m constantly finding myself in the next corner a little too hot, thinking, Whoa, how did that happen? No problem, just add a little more lean angle. Yeah, this thing’s just a big kitten.

Accelerating out of Spoon Curve, down the back straight, I’m feeling confident, like I’ve got a grip on things, so I give the throttle a hard twist. That’s when the beast awakens. With the tach reading just over 9000 rpm in fourth gear, the NSR leaps forward, my butt slams back into the carbon-fibre tail section and the bars shake side-to-side in my clenched fists as the front tire dances above the pavement. In the time it takes to find the tachometer, the needle is already into over-rev, so I stab a clutchless upshift and watch in disbelief as Mick’s monster eats up a fifth gear then sixth as quickly as you can read this sentence. Maybe quicker. Flip! How the hell did that happen? Who triggered the nitrous? Where’s the boost gauge on this thing? Okay, now breath again.

Then I realize a few things: that I am in fact pulling 12500 in sixth and that out of fear I inadvertently rolled out of the throttle a bit to keep the front end planted in fourth and then hadn’t whacked it fully open again, but I couldn’t tell the difference. Up until the back straight, I thought I was using two-thirds throttle squirting between corners, when in fact I hadn’t cracked the slides half-open yet – more like one-quarter to one-third and still getting more acceleration than I was ready for. As soon as the throttle is shut the NSR becomes a pussy cat again.

It takes me a full lap to get my courage back, but next time down the back straight, I’m twisting the throttle in anger again. All right, I’m ready for you this time. You don’t scare me. The front end dances through the top of fourth. I grab fifth at 12500 rpm, pin the throttle to the stop, and it settles down. Ha, Take that you sumbitch! Then the Beast teaches me lesson number two. At the top of fifth gear, at over 150 mph, it catches a rise and snaps the front wheel two feet in the air before I can back out of it. Okay, okay, anything you want. Just don’t do that again, please.

Recounting this to Mick Doohan his response is “We’re into sixth before the bump, but if I don’t keep my head behind the bubble I have to roll off, or it’ll come over backwards”.

Short shifting has almost no effect other than to produce longer, larger and faster wheelies. Holst says that with hindsight he was taken for a ride rather than that he was actively riding the Beast.

As a parting shot, he asked Mick how, by all that is Holy, he manages to ride the bike so fast. His response, “I only use the high rpm anyway – from maybe 9500 to past 13000 rpm. Before the Big Bang, we used maybe 11000 to 12500. At the higher revs, the wheelspin is more controllable because you are above the torque peak and you have a chance to catch it most of the time.

At the lower revs, it will likely kill you”. His three best pieces of advice for someone about to ride the NSR for the first time? “Well, definitely respect it, keep the revs up high to stay safe, and……………… Just try to stay on the thing!” Thanks Mick, but for me, I’ll get my jollies by watching, in sheer wonder, how you tamed the Beast!