Honda have the knack of bringing bikes to market that have enthusiasts scratching their heads. In recent times the NC 700/750 is an example of the point I am making. Down on horsepower but high on torque, the NC, on paper, was nothing to write home about, yet it took the market by storm. It’s simple formula with utility space where the tank lives and excellent fuel economy, proved an instant success for commuters and middleweight tourers alike. Clearly the factory marketing boffs know something we don’t. So it was in 1975 when the first Goldwing, the GL 1000, exploded onto the scene. The Honda faithful wanted a fire breathing thousand to take the fight to Kawasaki’s 903 cc Z1. Honda, in their wisdom, chose a different route.

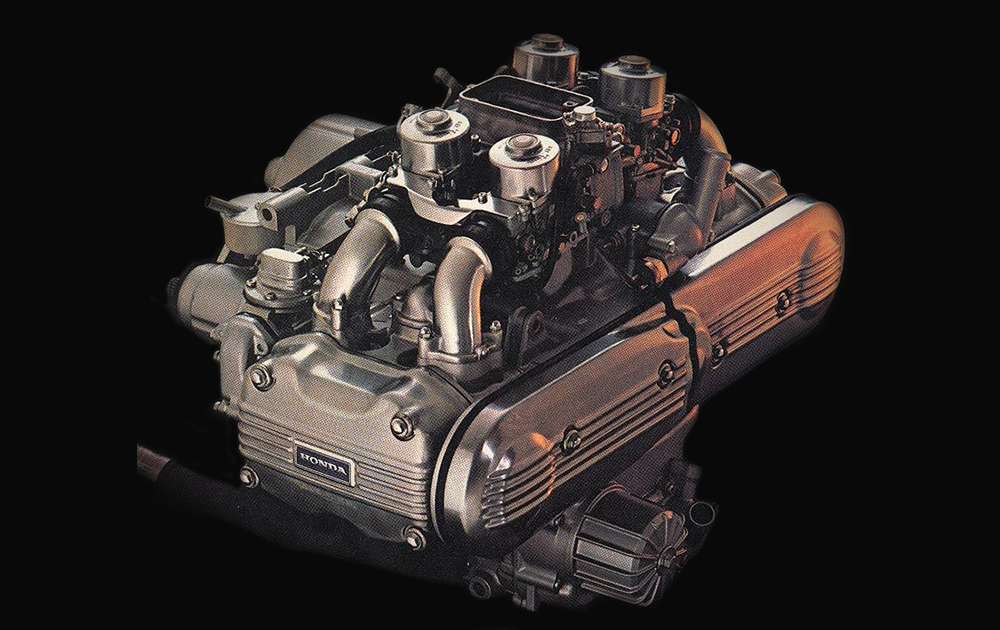

Honda noticed a subtle shift in American motorcyclists behaviour. BMW and certain Harleys were attracting a growing number of riders wanting to tackle long-distance touring. Honda had already established a reputation for reliability, so they figured that a smooth, reliable shaft drive bike which would be easy to service would be just the ticket. They had already developed a water-cooled, flat-six, single overhead cam engined bike, code named the M1. The project leader was an engineer named Soichiro Irimajiri who had designed the 6 cylinder Grand Prix Hondas of the ’60s. It was decided to go the touring rather than the sporting route. In order to shorten the bike the engine lost two cylinders and came to market in 1975 as the flat four-engined GL 1000.

The first Wing was a revelation. Absolutely nothing the world had ever seen [or ridden] was so devoid of vibration. The alternator spun in the opposite direction to the crank, negating the Bee Emm torque reaction when the motor was revved at standstill. It had a fat 4.50 x 17 back tyre with a 3.50 upfront. The fuel tank was under the seat to emphasise the low centre of gravity already enhanced by the flat-four engine layout. It was heavy, at around 265 Kg’s dry, but did not feel so. Americans, in particular, took to the Wing in droves. Touring accessory manufacturers started building a line of accessories to make the GL an even better tourer. Windjammer sold fairings by the score. The Wing, over time, morphed into an 1100 and was made available in “Interstate” guise as a full-dress tourer. The engine got two more cylinders as the GL 1500, going back to its original design roots.

Honda solved the length issue by using the same technology as on their VFR 800. They mounted the radiators in the side of the fairing rather than in front. In its current form, the Wing has an engine of 1833cc’s, with perfectly square bore and stroke, pumping out 125 HP @ 5,500 revs and 148 Nm of torque at 4,500 rpm. Fuel injection is flawless. The test unit was the six-speed manual gearbox option as opposed to the 7-speed DCT. The gearshift is light and accurate. The big wing has a reverse gear function operated by a button on the left handlebar. Neat. As good as the manual is, I suspect that the DCT would be even better. Attacking the sweeps blipping through the paddle shifters would be amazing and then just leave it in auto for cruising.

The GL 1800 is a magnificent looking motorcycle. Resplendent in a candy apple metallic red it looks sleek and sporty despite its size. Topbox and panniers are integrated into flawless bodywork. The finish is of a standard that only Honda can produce. Simply off the charts! The exhaust pipes are triangulated to maximise cornering clearance. They tuck in tight around a 200/55 x 16 rear wheel. Upfront is a 130/70 x 18 suspended from a single shock wishbone type of suspension. The back suspension is Hondas Pro-Link with a single-sided swingarm. The seat is at a low 740 mm and wide and comfy. The rear perch offers genuine armchair comfort. Both seats have five levels of heat adjustment. A fantastic feature on a chilly ride. The fuel tank is only 20.8 litres which could be a bit small were it not for the superb fuel economy of the big Goldwing. More on that later. The Wing weighs a hefty 357 Kgs fuelled.

Common to this genre of Super tourers, the Wing has an onboard radio with speakers mounted in the fairing as well as in the rear seat surround. Adjustments can be made via the left handlebar or a central tank console. Whilst I am admittedly BC [before computers] I simply could not get the hang of the various adjustments and settings. Unfortunately, I did not have access to the bike’s manual, so I could not study up on the operation. Suffice to say it was not intuitive to me. It took me four fillups before I managed to reset the trip meter. No big deal. A day with the manual and you will suss everything out.

For me, it is all about how the bike performs. Bloody hell! This big Wing performs! The flat-six mill is sublime. Torquey and beyond smooth. If you have never ridden a Wing, you just don’t understand smooth! Rev it a little and it responds in wonderful fashion with a silky thrust that never fails to thrill. At 3000 rpm in top gear using half the available revs, the Wing is rolling at 140 kph. At this speed, it returns 5,7 litres/100 two-up with luggage. Roll into the mountains and the fun factor increases. I set the electronic suspension to two-up with luggage, which is the setting you can frankly just leave the Wing in and have done with it. Despite limited suspension travel, the Wing does an admirable job of handling bumpy roads. At times it can feel a little like a big scooter with a rather choppy ride, but this only manifests over really crappy surfaces. For the most part, it maintains its composure admirably.

Mountain passes are a hoot. Drop a gear or two and let the Wing sing. Pitch it into sweeps and turns and nothing touches or scrapes other than the very occasional footpeg feeler. The smooth thrust from the magnificent motor powers you through bends and past slower traffic effortlessly. Very little can ruffle the Wings’ feathers! I tended to leave the engine in tour mode but on occasion selected “Sport” for the sharpened response. Awesome! Sport mode does tend to accentuate slight driveline lash. This tends to be ever so slightly more pronounced in shaft driven bikes with less forgiving drives than the cush rubbers in the hub of a chain-driven bike.

The screen adjusts electronically to allow you to look over or through it. Irene complained of buffeting with it on the lower settings, so I jacked it up and we boogied along in absolute comfort. That said, my body required some adjustment to the relaxed riding position of the Wing. The optional backrest for the rider would be just the ticket. The excellent handling and sporty nature of the Wing means that you do not get frustrated no matter where you are riding. Trundle down the motorway or sweep through the mountains, it’s all in a days work for the wonderful Wing.

You cannot ride this bike on a breakfast run and do a review. You need to ride it like it was designed to be ridden. Two up and very far. We did just that. We travelled down to Hazyview in Mpumulanga via Long Tom Pass. The next day we rode through Swaziland to Big Bend, strafing endless sweeps at high speed.

Our third day was cool and overcast as we cruised south to Durban. After visiting with friends we negotiated Durban rush hour traffic then headed up to the Nottingham Road Hotel. This proved a testing ride for the Wing. It started to drizzle as we left Durban on the N3. The clouds descended until we were riding in fog. The temperature, which was cool all day, now plummeted to 8 degrees and the gloom gave way to dark. Since the demise of our railway system, our roads are inundated with trucks. Close to zero visibility, road works, trucks, cold and slick roads. A veritable sh*t show! The Wing was incredible. It kept us warm and snug and safe as it handled the conditions with aplomb, giving me confidence despite the treacherous conditions.

Irene dialled her seat heat up to five and sat high and dry. It was a relief to pull into Notties and sip on a glass of red in front of a roaring fire. The next day’s ride was down to Howick and then to Himeville with the Wing railing through the sweeping bends with me in semi attack mode, not believing what the Wing is capable of. More of the same the next day. Bergville, Oliviershoek Pass and through Golden Gate to Clarens. The last day was 2-degree temperature out of Clarens, gradually warming as we rolled back to Pretoria. 2454 kilometres of Goldwing glory. What a bike!

The big Goldwing is incredibly capable. If you want to travel fast and far with your significant other, in sublime comfort, then it is hard to think of anything better. It is not perfect. What bike is? The display can be improved and simplified. The panniers should have inner bags as standard.

It needs an integrated GPS, but really those are minor issues. Honda can be justifiably proud of what their wonderful Wing has evolved into. The Guinness World record for the most distance around the world on a motorcycle is held by a Goldwing. Our own Des Pistorius clocked over one and a quarter million kays around SA on his Goldwing Interstate. Testimony to Honda engineering at its best.

Super tourers like the Wing may not be every bodies cup of tea, but it remains at the very pinnacle of two-wheeled tourers. Given enough space [and enough ammo] there would be a GL 1800 in my garage. At around R380000 it doesn’t come cheap, but amortised over the years of pleasure it will give you and the Missus, it is probably a bargain! WELL DONE HONDA.